Benthic macroinvertebrates: the little creatures that live at the bottom of a body of water—worms, small crustaceans, snails, insect larvae—things like that.

Because they're sensitive to a variety of environmental disturbances, monitoring the number and diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates in residence has long been used as an important indicator of the health of a particular body of water.

Knowing which is which

While they are generally big enough to be visible to the naked eye, identifying benthic macroinvertebrates can still be difficult—and accurate identification is important in monitoring because different species are sensitive to different stresses.

In Atlantic Canada, a pair of researchers and their team—one at the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) in Moncton, New Brunswick and the other at Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) in nearby Fredericton—is showing how genomics can improve biomonitoring by making identification of these creatures more accurate, as well as faster and less expensive.

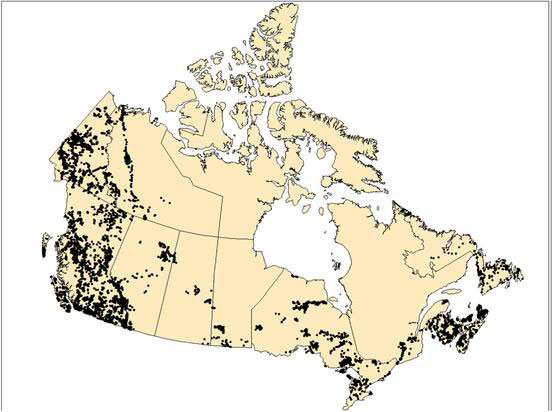

Map of Canada showing Canadian Aquatic Biomonitoring Network (CABIN) monitoring sites.

The project

With funding through the Government of Canada's Genomics Research and Development Initiative (GRDI), DFO Research Scientist Nellie Gagné and ECCC Research Scientist Dr. Donald Baird are examining macroinvertebrates collected from the bottom of lakes, rivers and streams throughout the Atlantic provinces, and doing a side-by-side comparison of 2 methods of identifying each specimen.

"We're using the traditional method of identification—looking at a specimen through a microscope," explains Ms. Gagné, "And we're using genomics technologies to identify a specimen by comparing its DNA to the DNA of the thousands of species that have been catalogued as part of a major international effort, which includes other GRDI-funded projects."

Genomics does have its advantages

"Even with a microscope, it can be difficult to spot the subtle differences between species," says Ms. Gagné. "In some cases, only a few people in the entire country have the expertise to tell one from another."

On the other hand, as Dr. Baird explains, DNA metabarcoding using high-throughput sequencing provides more information, more accurate information—and in much less time: "It's an oversimplification, of course, but in essence, with this technology, you drop a biological sample from the bottom of the river into the machine, and in a short time, you have the DNA of every species in that sample—without ever looking at the animals directly," says Dr. Baird.

A team of researchers from DFO collect samples from a stream in PEI as part of the GRDI research into biodiversity of benthic macroinvertebrates. (photo: Keila Miller, PEI Wildlife Federation)

Biomonitoring 2.0

The health of Canada's freshwater resources is monitored by CABIN—the Canadian Aquatic Biomonitoring Network. Led by ECCC, members of this national partnership include provincial and territorial governments, academics, Indigenous communities and many others, who provide CABIN with samples from lakes and rivers across the country.

At ECCC's Atlantic Water Quality Monitoring and Surveillance office, Head of Special Projects Vincent Mercier says the GRDI research promises a dramatic increase in the type and amount of information CABIN can provide to support evidence-based decision-making by policy-makers and regulators.

"With traditional methods, it's impossible to see and identify everything," says Mr. Mercier. "With these genomics-based methods, you get the whole picture. It enables what you might call biomonitoring 2.0—allowing you to see much more subtle impacts of environmental disturbances. We're only just beginning to understand the kinds of things we can do with this new information."

Adding new knowledge

That new information includes a better understanding of what salmon and other fish have been eating, adding a new dimension to freshwater biomonitoring.

As Ms. Gagné points out, it's not easy to figure out what a fish has been eating just by looking at the contents of its stomach. "Now, based on the DNA in their stomachs, we can see exactly what the fish have been eating," says Ms. Gagné. "And how changes in the biodiversity of these invertebrate populations can impact on salmon and other commercially important fish species."

Cross-government collaboration

The research project led by Ms. Gagné and Dr. Baird is part of one of the largest research projects ever undertaken by the federal government: the 5-year, GRDI Ecobiomics Project, launched in April 2016, involves 64 federal scientists at 7 departments and agencies working on 16 separate but interlocking research projects.

The Ecobiomics Project is aimed at taking advantage of the potential of genomics to better understand and characterize the enormous diversity of microorganisms and invertebrates that are responsible for sustaining the health of soil and water quality—knowledge that can deliver benefits ranging from more effective environmental protections to more productive and sustainable agriculture.